The Socratic seminar is not always all it’s cracked up to be. Read this other blog post to learn why. Then come back to this blog post with my tips for using Socratic seminars in your class.

1. Create a safe and comfortable atmosphere in your class before trying a Socratic seminar.

Students need to trust each other and feel comfortable and connected before they risk speaking their minds. I do a lot of icebreakers and team-building activities with my students before ever trying a Socratic seminar with them.

2. Prepare students for success.

Be sure your students know what a Socratic seminar is, including its purpose, components, and the possible steps to follow. Here’s a great lesson that gives a good Socratic seminar overview.

Then assign a variety of reading and note-taking in advance. Try to use several texts with various perspectives, if possible, and consider assigning different students different texts to read to make your discussions richer! Even if your class all reads the same novel, you might be able to find different literary reviews for your students to read (videos could be included). This is important because if your students come from the same neighborhood and cultural background, they may already have very similar viewpoints. You could also ask them to each find and read two articles with opposing viewpoints.

Teach students how to mark their text and/or take focused notes and ask them to bring a few related open-ended questions for discussion.

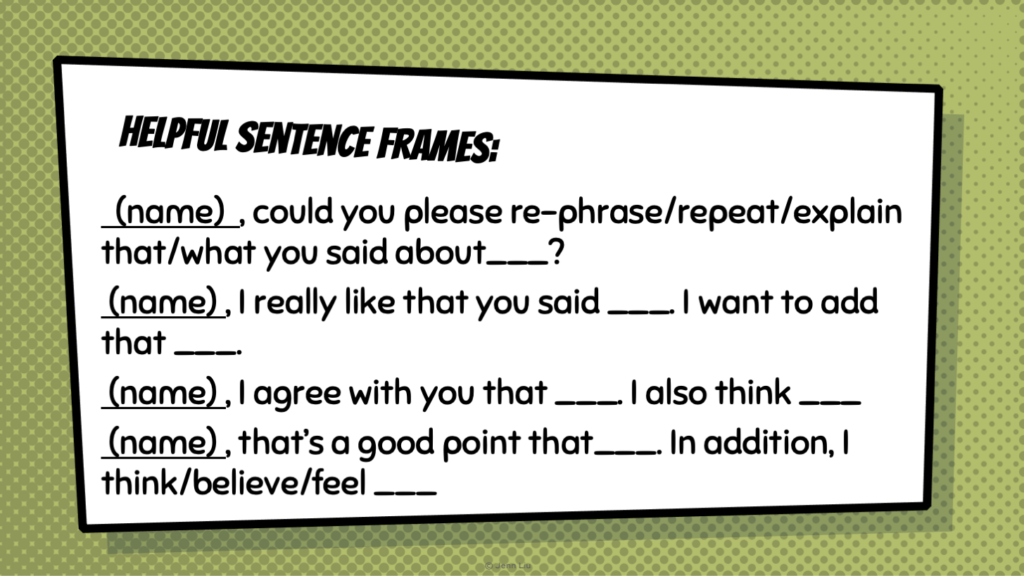

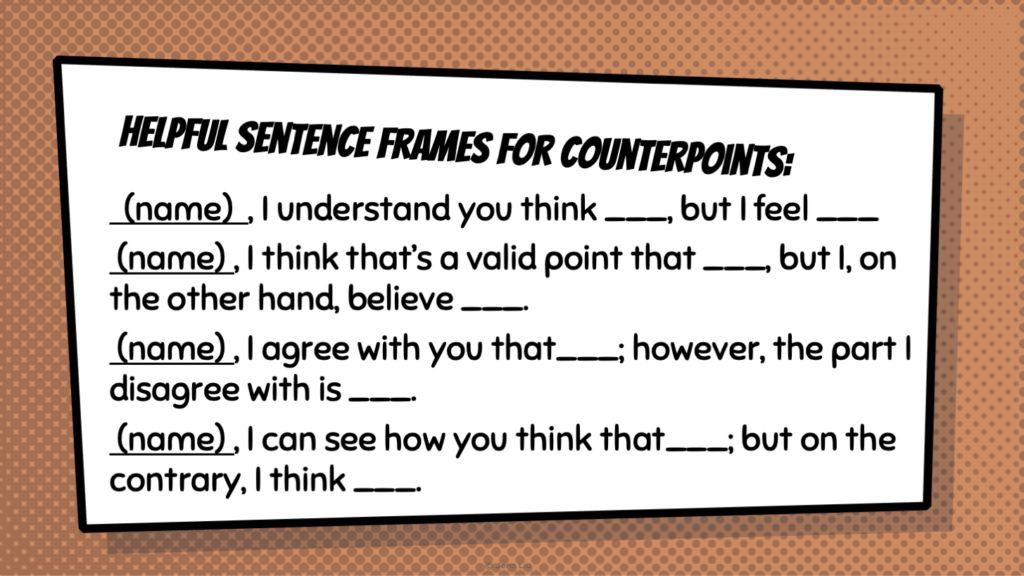

3. Teach students academic vocabulary, useful sentence frames for sharing their opinion, and clarifying questions to ensure understanding.

You can do this using anchor charts, modeling, and keeping useful phrases posted in class. For instance, you can post verbs for referring to a source such as implies, demonstrates, claims, indicates, argues, etc. and sentence starters such as the ones below.

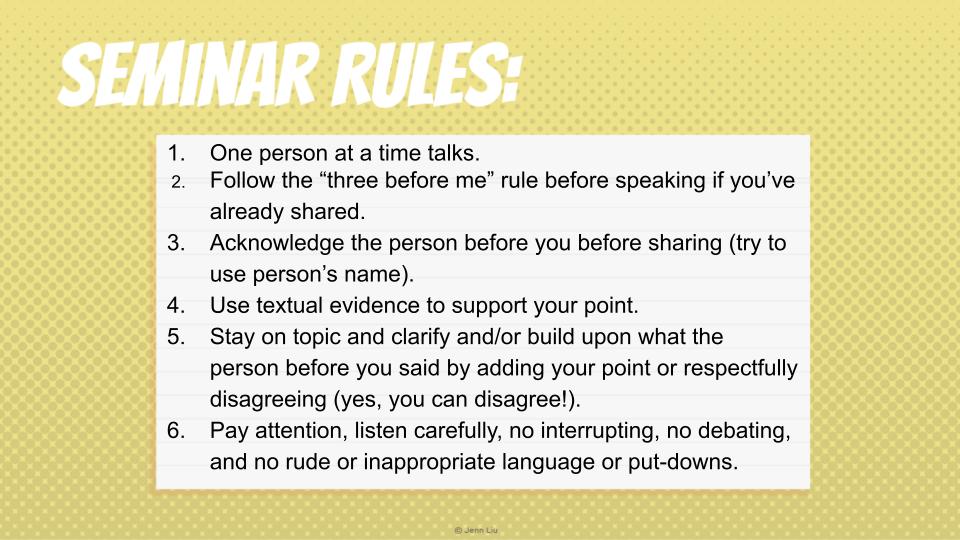

4. Emphasize a structure with rules.

First, there is the physical structure for group discussions, which is typically a circle to establish equality among members. If your class is online, you could have students place avatars in a circle on a digital whiteboard or Google slide and move their avatar to speak. I’ve never done this myself but heard this idea from some teachers. A circle may not be necessary or work with other online formats.

The other structural components of a good seminar include following a process beginning with an engaging essential question followed by tip #2 and 3, reviewing rules (see my example below), and then following a turn-taking pattern led by a student facilitator/moderator when in groups. The structure should be flexible and negotiable depending upon how comfortable your students are with each other. This structure is what makes a Socratic seminar different from less formal small-group discussions. The small-group Socratic seminar ensures turn-taking and stresses using academic language and textual evidence.

I’m sure you’ve heard it before — students like structure!

5. Move discussions from pairs, to small groups, to a fishbowl format.

I recommend always starting any discussion with a simple “think-write-pair-share” to give students the chance to think and write to clarify their ideas and then safely share and rehearse with a partner. For example, on your Socratic discussion day, you could say: “Please take out your notes and look at the questions you came up. Take a couple of minutes to think about what you are asking and why, and jot down a few notes. Then share your questions with a partner. For now, just share your questions but you don’t need to answer them just yet.” Of course, you could also have them try to answer their questions.

Then you could ask a volunteer to share a question with the whole class.

Next, you could say: “Now, look over your notes again and find a point related to this question that stood out for you. Think about why that idea stood out for you and jot down a few notes. Then share this with your partner.” You could have students stick with the same partner they previously had or move to a new one. In fact, you could continue with this by having students share new questions and then move in the opposite direction in two lines facing each other, e.g., doing a “give one, get one” exchange of ideas or “bounce” ideas off their partners. If you do this, it might help for students to carry a clipboard or notebook to write on.

If you’d like to continue the discussions, I’d have your Socratic seminars in small groups of five to six students (this number allows students to hear various perspectives but is still small enough for students who struggle with speaking in much larger groups). This format might be contrary to the idea that a Socratic seminar should be a whole class discussion, but it could save a lot of students from experiencing extreme feelings of social anxiety and instead, get them to share a lot more.

While extroverts might not relate, social anxiety feels real to more introverted students. Having to speak in front of the whole class without enough warm-up can be so nerve-wracking for some students, they’d rather take a zero than do it. It’s true — I’ve seen it happen.

But then how is having a Socratic seminar in small groups different from informal small group discussions? See number 4.

If your students already did a good exchange of ideas using the two lines facing each other strategy, you may not feel it necessary to move to a whole-class discussion. But if your students feel ready or request it, you could try whole class “fishbowl style” seminars. I like using the inner and outer-circle format because you can have students pair up, which is more comfortable for many. With this format, the inner-circle students participate directly in the discussion but can confer with the outer-circle students before sharing. Again, you may not feel the need to ever have a whole class discussion, especially if you already did the two lines facing each other discussions.

As an alternative to the fishbowl discussion, you could just have volunteers share with the whole class following the small group discussions.

6. Hang back and let students facilitate larger fishbowl-style discussions.

You might have to model facilitation skills in the beginning, e.g., muting dominant voices and encouraging reserved students, but then gradually release discussion leadership to your students. Ask for volunteers to facilitate or moderate discussions and encourage turn-taking so the same students are not always the facilitators. I like to use the “three before me” rule. In smaller groups, this might have to be “two before me.”

As I mentioned in the blog post I recommended you read before this one, I try to put on my poker face and hang back during student discussions, letting students facilitate on their own. However, sometimes the teacher has to step in. If your class is discussing sensitive issues, there is always the chance a student could say something highly offensive, such as a racist or sexist comment.

If this ever happens, I’d still wait and see if another student speaks up to point out the offensive comment (you could train your moderators to watch out for this). If not, depending on the severity of the comment, I’d intervene with a reminder about the rules. If the comment or language is highly offensive, I’d definitely pull the student outside for discussion or address the issue as soon as possible (I try not to confront students in front of the class).

7. Make it clear that students don’t need to agree with each other.

This is when they risk going into groupthink, especially if you have a homogenous class or students who for whatever reason, be it culture, personality, or upbringing, tend not to make waves. Encourage critical thinking and friendly and polite disagreement!

8. Don’t give students points for how or how much they participate.

When you give students a point(s) for each time they speak, they may end up being redundant or less thoughtful about what they say. Instead, I’d give students points for being prepared with notes and questions. I’ve actually postponed discussions because not enough students were ready. Also, when students are prepared, they’re more willing and excited about participating.

If you feel the need to grade seminar participation, then I’d have students self-assess themselves on a rubric (see #10). This way, the discussion won’t feel so much like a competition to speak just to get points and students are more likely to share valuable insights. This also makes grading easier for you. From my experience, students are very honest and fair when they grade themselves.

9. Don’t always make your seminars into oral discussions.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, teachers and students have become much more comfortable and knowledgeable than ever using technology and online platforms for discussions.

There are many apps to choose from. If you want something free, a Google slide will do (you’d be amazed how much you can do on Google Slides). The free version of Padlet is limited so many teachers find it worth it to get a paid subscription (check out all these Padlet ideas, especially #8 on the Padlet link).

To conduct a Socratic seminar online, you could have students post their comments on a shared slide, either using a digital whiteboard app or Google or Padlet slide, and then leave comments for each other. Or they could participate in breakout rooms and then later as a whole class.

Some strategies for online discussions and reducing onscreen stimuli and avoiding online fatigue are:

• Try putting yourself out of view for part of the class.

• Don’t force students to turn on their cameras all the time.

• Ask everyone to use plain backgrounds when cameras are on.

• Tell students to put away their phones and close other tabs so they are not distracted and overstimulated by multi-tasking during class.

• Enable “speaker view” instead of “gallery view” to avoid looking at everyone the whole time.

Try different formats (small group, fishbowl, whole class, and online) and then ask your students what they like best.

10. Allow students time to reflect and assess the seminar as a class and individually.

Talk about what went well and what needs improvement. Ask students how they felt, what they learned, how they changed, and what they want to try the next time.

Click here to get my FREE Socratic Seminar rubric, which can also be used for self-assessment. You might also like this complete Socratic Seminar Lesson Plan.

Don’t forget to read this other blog post: Would You Like to Know What I Really Think about Socratic Seminars?

If you found this article helpful, share it with your teacher friends and colleagues!

Bold font